Well, I've finally emerged from various Christmas Island induced rabbit holes and we can have our virtual trip to look at some of the special birds of this remote island. There aren't any feral rabbits on Christmas Island, so Red Crab burrows might be a better metaphor.

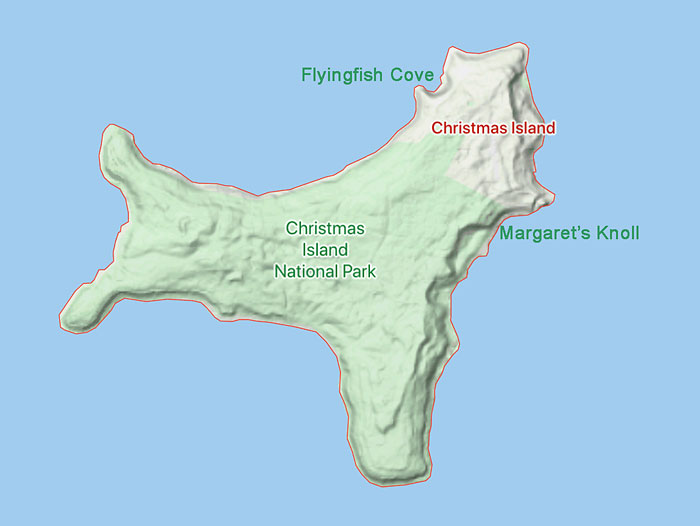

Christmas Island is both remote and very old, making it an interesting place in terms of both biogeography and avian evolution. It is about 350km/220 miles south of the western tip of Java and 1,550km/960 miles northwest of Exmouth in Western Australia. There are no nearby islands - the Cocos Keeling Islands are 980km/610 miles to its west. It first appeared about 60 million years ago as a 5,000m/ high volcanic seamount which then underwent several geological uplifts over the following 10 million years giving it a layered structure with cliffs, both coastal and farther inland, formed by coastal erosion. Coral reefs deposited limestone over the basalt core.

60 million years ago was shortly, geologically speaking, after the extinction event, thought to be a global collision with a large object, about 66 million years ago that marked the end of the Cretaceous period. This caused the extinction of many plants and animals, notably the dinosaurs, and resulted in rapid adaptive radiation of many surviving groups, particularly birds and mammals. At the time Australia was still attached to Antarctica and the other tectonic plates of the former Gondwana were still drifting to their current locations and resulting land masses: South America, Africa, Madagascar and India.

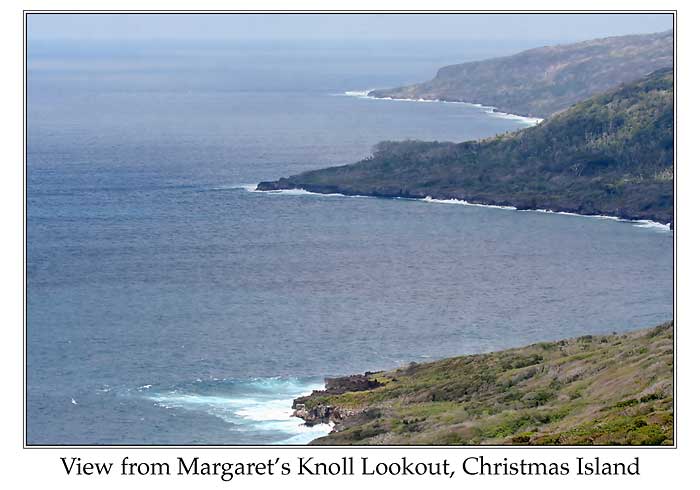

The island has an area of 135 sq km/52 sq mi and the coast is an almost continuous cliff with few bays or beaches, as shown in the photo of the east coast. Although known to European sailors from the 17th century, the cliffs made landing, exploration and settlement difficult and it remained uninhabited and consequently undisturbed until the late 19th Century. The largest bay is Flyingfish Cove near the north of the island where the Settlement is located. The photo below shows a typical stretch of coast looking south from Margaret's Knoll on the eastern side of the island.

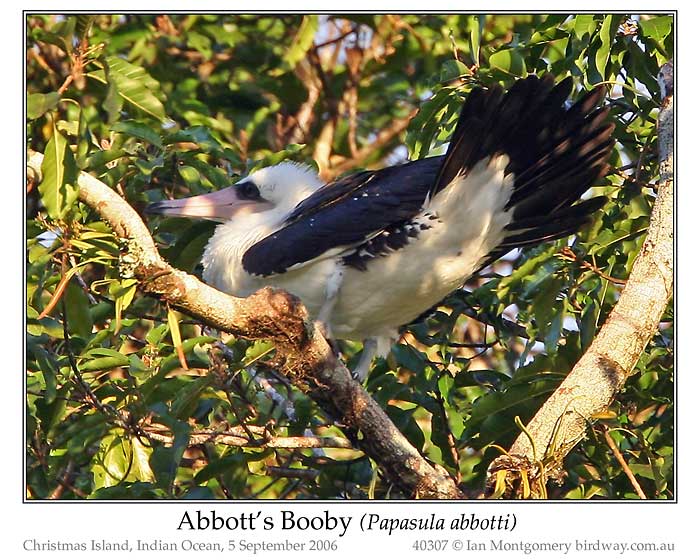

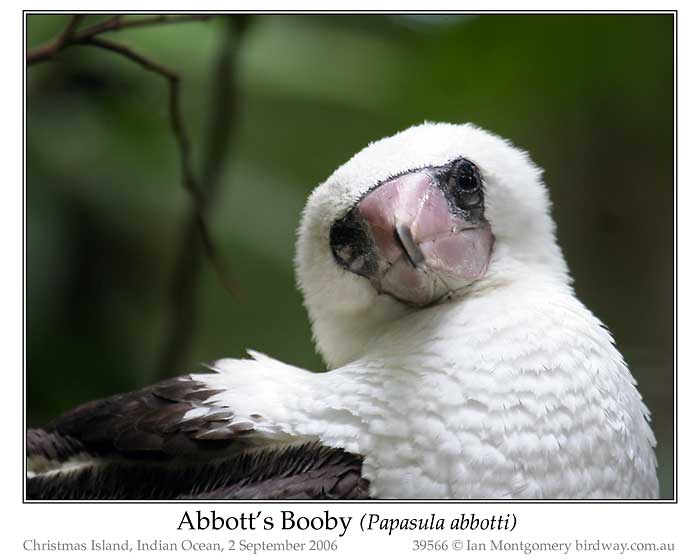

You'll probably know from previous posts that I'm particularly interested in the evolution and ecology of birds, and by extension their taxonomy and biogeography. Isolated islands both provide fascinating insights into and pose intriguing questions about both evolution and biogeography and I'm going to look at the species on Christmas Island from these angles. We'll start with the taxonomically most unusual, Abbott's Booby, which belongs to a monotypic endemic genus, then look at other interesting seabirds and finish with land birds.

Three of the seven global species of Booby breed on Christmas Island: Abbott's, Brown and Red-footed. Both the Brown and Red-footed are widespread, found throughout tropical waters around the world and members of the genus Sula which comprises all the species of Booby except Abbott's. Abbott's, however, breeds only on Christmas Island and is the only member of the genus Papasula. It was originally included in Sula but structural differences between it and both Gannets and other Boobies led Olson and Warheit 1988 to move it to a new more primitive genus of its own. Subsequent DNA studies have confirmed this and Papasula is thought to have branched off the early Gannet-Booby lineage about 22 million years ago.Three of the seven global species of Booby breed on Christmas Island: Abbott's, Brown and Red-footed. Both the Brown and Red-footed are widespread, found throughout tropical waters around the world and members of the genus Sula which comprises all the species of Booby except Abbott's. Abbott's, however, breeds only on Christmas Island and is the only member of the genus Papasula. It was originally included in Sula but structural differences between it and both Gannets and other Boobies led Olson and Warheit 1988 to move it to a new more primitive genus of its own. Subsequent DNA studies have confirmed this and Papasula is thought to have branched off the early Gannet-Booby lineage about 22 million years ago.

We can't, however, conclude that it evolved in isolation on Christmas Island. The species was first described from a specimen collected by the American naturalist William Louis Abbott in 1892 on an island near Madagascar in the western Indian Ocean, either Assumption Island or the nearby Glorioso Island. Fossil evidence indicates that it was quite widespread in the Indian and Pacific Oceans and there are eyewitness reports of it breeding in the Mascarene Islands near Mauritius (as described in Wikipedia). So its endemic status on Christmas Island is a result of its extinction elsewhere. On Christmas Island the population, currently estimated at about 2,000 pairs, has declined owing to habitat clearance and the species is classified as endangered.

Here, by way of comparison, is the white morph of the Red-footed Booby. There is also a widespread brown morph of this species but all, or almost all of the ones on Christmas Island are of the white morph. You can see photos of the brown or dark morph here: Birdway Red-footed Booby.

Frigatebirds are very well represented on Christmas Island. Three of the five global species nest on the island: Lesser, Great and the endemic Christmas (Island) Frigatebird. The other two species are the Magnificent (Birdway: Magnificent Frigatebird) of Atlantic and eastern Pacific Oceans and the Ascension, endemic to Ascension Island in the Atlantic. The Lesser (Birdway: Lesser Frigatebird) has colonised Christmas Island in small numbers relatively recently while the Great (Birdway: Great Frigatebird) is an endemic subspecies (listeri) with a population of about 3,300 pairs. The Christmas Frigatebird is globally the rarest with a population of about 1,200 pairs. The population has declined since human settlement and the species is now classified as critically endangered, both because of its small, declining population and the fact that its breeding range is limited to a single location.

Unlike Abbott's Booby, it's probably fairly safe to assume that it evolved on the island and differs from the other species of Frigatebird mainly in the patterning of the plumage. The male has a diagnostic white belly, while the female has a white breast and belly extending further down the belly than in other species.

Frigatebirds feed both by snatching prey such as squid and flying fish from on or near the surface of the water and by harrying Boobies, Tropicbirds and Terns until they drop their food. In the photo above, this female has just regurgitated a no doubt tasty mixture for its chick including a flying fish, the “wings” of which you can see sticking out on both sides of the chick's mouth.

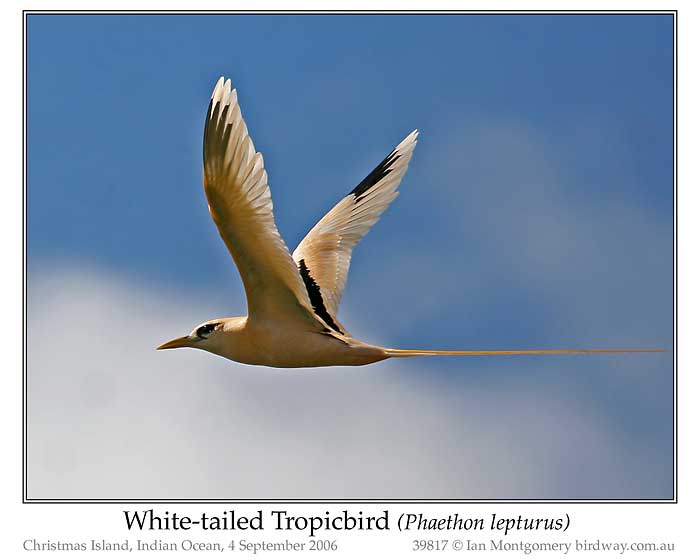

While we're on the subject of tropical seabirds, Christmas Island has two of the three global species of Tropicbirds: the White-tailed and Red-tailed Tropicbird. Most of the local White-tailed Tropicbird population has black and apricot rather than the typical black and white plumage and has been ascribed to a separate subspecies fulvus. It is known locally as the Golden Bosunbird. However, 7% of the local population has the normal black and white plumage and apricot coloured birds occur in small numbers elsewhere, so it may be better to consider the differences just as colour morphs.

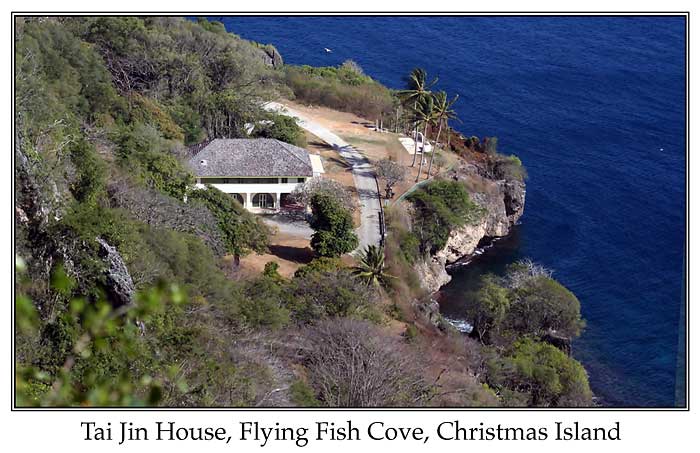

For me, the Golden Bosunbird was the most beautiful bird on the island and I spent hours watching them in flight from this lookout near the settlement overlooking Tai Jin House, below, the former resident of the governor in more colonial times.

The Red-tailed Tropicbird, or locally Silver Bosunbird, is quite beautiful too. In pristine condition, the birds have long red tail streamers, but these frequently get broken off when the birds are nesting. They do a spectacular fluttering display flight travelling downwards and often slightly backwards near the cliffs where they nest.

Both of these Tropicbirds are quite widespread. The White-tailed occurs in tropical parts of the Indian, Pacific and Atlantic Oceans while the Red-tailed ranges from the western Indian Ocean to the central Pacific.

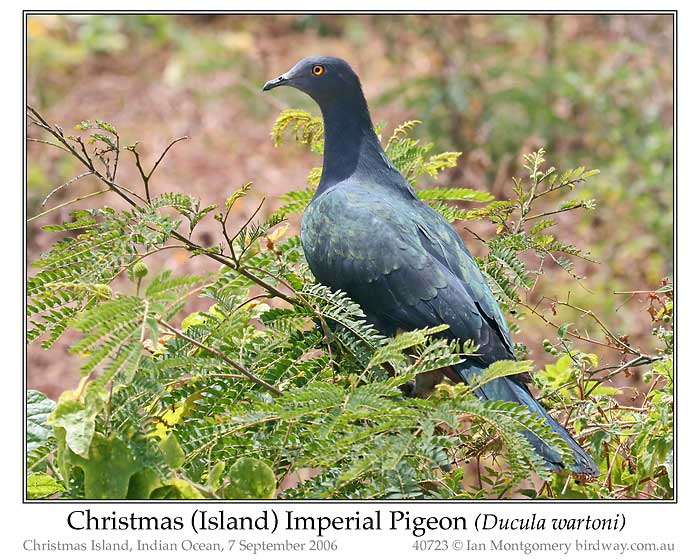

Special birds on Christmas Island are not restricted to sea birds: it has some unusual land birds as well. Here is the splendid and abundant Christmas Island Imperial Pigeon.

The dorsal plumage is this lustrous green which reminds me of Connemara marble. The breast is plum-coloured, the vent rufous and the eyes are a spectacular golden. It's endemic to the island and its closest relative is the Pink-headed Imperial Pigeon (D. rosacea), widespread in the Indonesian islands of the Java Sea.

A much more elusive member of this family is endemic race natalis of the Common or Asian Emerald Dove. This used to be treated as the same species as the Emerald Dove that occurs in Australia but the latter has been split into two species: the Common or Asian and the Pacific. As a result, Christmas Island is the only place in Australia where the Common or Asian species occurs.

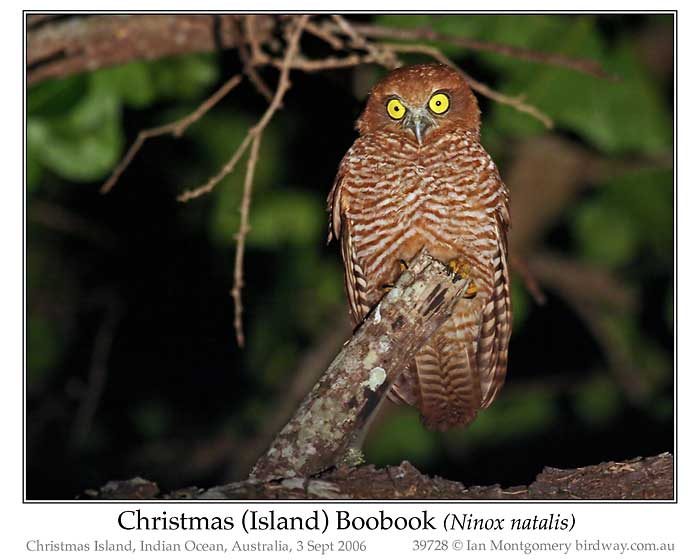

Also elusive is the only resident owl, the endemic Christmas Island Boobook. With a length of 26-29cm/10-11.4in, it is generally smaller than the rather variable Australian Bookbook of the mainland: 27-36cm/10.6-13.8in. We went out one night near the golf course with David James, one of the leaders of the first Christmas Island Bird Week, who was armed with a recording of the call. The recording was of poor quality but to our delight and surprise we got a response and a family of three appeared at close quarters. The species is regarded as vulnerable with a population of maybe 500 pairs and there are concerns that the introduction of yellow crazy ants is affecting the availability of the invertebrate prey that is its main source of food.

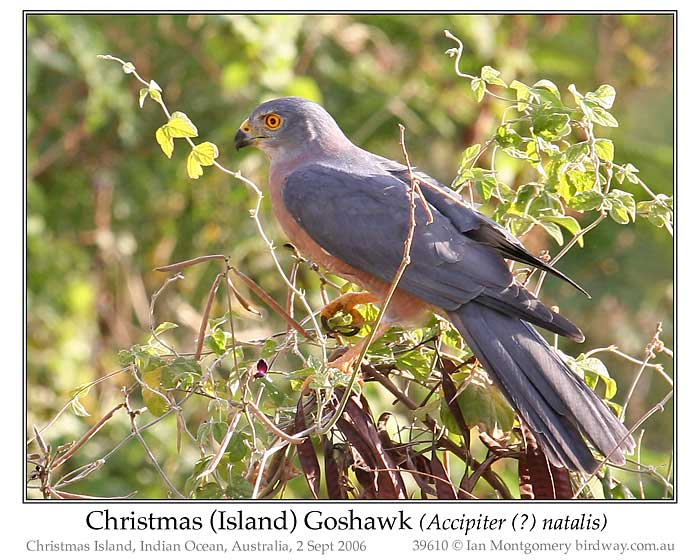

Christmas Island also has an endemic diurnal predator, the Christmas Island Goshawk. Its taxonomy has proved a challenge for various taxonomists and it has generally been treated as a race of the Brown Goshawk (Accipiter fasciatus). In fact there are significant differences in structure, appearance and behaviour, so there is probably justification for treating it as a separate species. It is the rarest of the endemic birds with a population of probably less than 250 individuals. Unlike the Brown Goshawk, the birds are relatively tame and approachable.

Christmas Island has only two endemic Passerines, the endemic race of the Island Thrush that was the subject of the last Irregular Bird and the Christmas Island White-eye. White-eyes are famous for finding their way to and settling on remote islands so there are nearly one hundred species ranging from Africa through the warmer parts of Asia to Australasia and the islands of the Pacific. This one is posing on a coral tree near Tai Jin House.

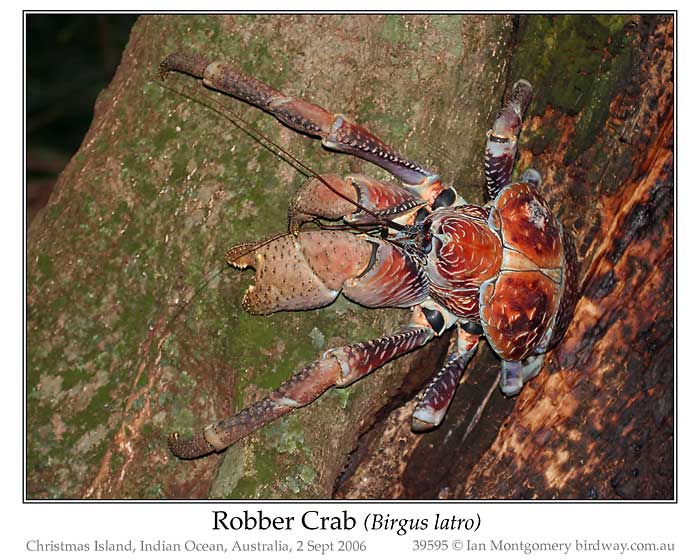

So, there you are. Plenty of rabbit or red crab burrows to be explored by budding taxonomists and biogeographers. Talking about Red Crabs, itt wasn't the right time of the year for the Red Crab spawning event and I don't remember seeing any as they keep out of sight at other times of the year. We did encounter some Robber or Coconut Crabs, however. This species is the largest terrestrial arthropod, weighing up to 4kg/8.8lbs and measuring up to 1m/39in in span from leg tip to leg tip. Their range comprises islands of the Indian Ocean and parts of the Pacific.

Greetings and stay safe

Ian

Join the The Irregular Bird Club

Birdway has a free Irregular Bird - formerly Bird of the Moment/Week - Club, enjoyed around the world since 2002 by currently 1000 members. An illustrated article is sent to club members at intervals. The photos are significantly better quality images than those on this web page which are compressed more for faster loading.

The club is a Google Group called Birdway to which only Ian can post. To join the group, enter your email address in the Google box below and click the Join button. This will take you to the Google Group joining page for confirmation. Alternatively, email Ian directly using the Contact link below and he'll gladly do it for you and answer any questions.

Ian also uses the Irregular Bird to keep club members up to date with developments, such as improvements to the website and publication of ebooks. He will not reveal your email address to anyone else nor use it for any other purpose.

Page revised on 11 August 2020

Hide

Hide