Back to South America this time for a flightless Ratite, the Greater Rhea (Birdway: Greater Rhea), a species I was very keen to photograph. Later we'll consider the other southern continents in the context of the eclectic collection of species that make up the other (mostly) flightless Ratites such as the Ostrich and the Emu.

The Greater Rhea, the largest and most widespread of the three sorts of Rheas in South America, wasn't numerous in the Pantanal and seemed to be confined mainly to the drier parts of the northern part. However, they weren't hard to see and we usually saw them in pairs. They were much bigger than I'd expected, like smallish Emus. I'd seen a photo long ago of Rheas running through the pampas of Argentine at speed and appearing, I though then, closer to the size of bustards. Greater Rheas are 127-140cm/50-58in in length and weight 20-25kg/44-55lb, compared with Emus at 150-190cm and 30-55kg, and Australian Bustards at 90-120cm and 3-8kg.

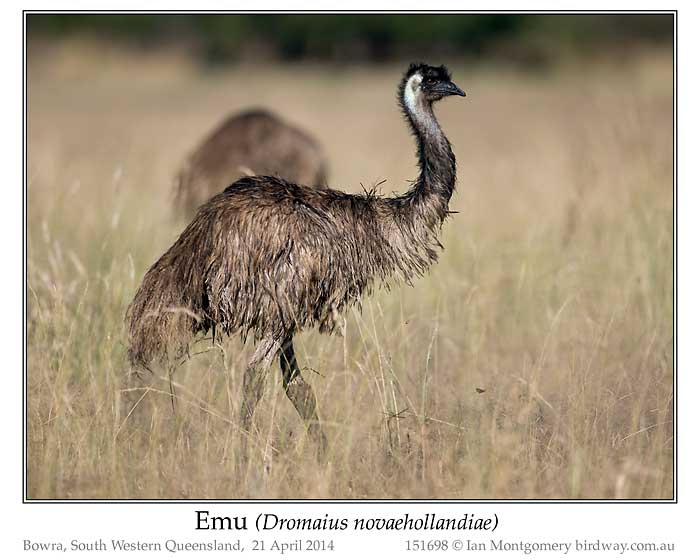

Considering they're not closely related, I was surprised at how like Emus they looked, though with more delicate features and larger fluffier feathers, more like feather boas than the shaggy, old sheep fleece look of Emus (see the fourth photo). The Greater Rhea is quite widespread through central South America east of the Andes with a range comprising Brazil south of the Amazon Basin, eastern Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay and a big chunk of northern and eastern Argentina.

There are two or three species of Rhea. In southern Argentina and neighbouring areas of eastern Chile, the Greater Rhea is replaced by the Lesser Rhea (Rhea pennata) 90-100cm and 15-25kg. Maybe the photo that I had seen long ago was, on second thoughts, of members of this species. The third candidate, the Puna Rhea (Rhea pennata tarapacensis or Rhea tarapacensis), is similar to the Lesser Rhea, also 90-100cm and 15-25kg, perhaps conspecific. It replaces the Lesser and Greater Rheas in northwestern Argentina, northeastern Chile, southwestern Bolivia and a small area of southeastern Peru. Both the Lesser and Puna Rheas have brown feathers on the back with white edges which give them an attractive scalloped appearance.

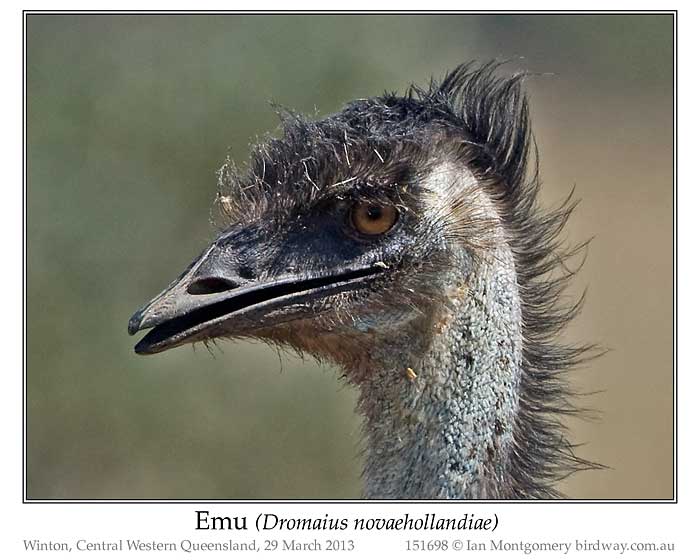

Back in Australia, the Emu (Birdway: Emu) has a widespread distribution through mainly on the mainland. Only the mainland race survives, other forms, usually now considered races rather than full species, having been hunted to extinction since European settlement in Tasmania, King and Kangaroos Island. The mainland race has been successfully introduced to both Kangaroo Island and Maria Island off the east coast of Tasmania.

Australia and New Guinea have three species of the rather different but related and also flightless Cassowary, with the Southern Cassowary (Birdway: Southern Cassowary) being the only one occurring in Australia.The Cassowary photo shows a watchful father taking his confident child for a walk along the beach as a change from the usual habitat of tropical rainforest in northern and northeastern Queensland. Interestingly in most species of Ratite, the males alone incubate the eggs and take care of the young, with the only exceptions being the Ostriches and some species of Kiwi, where the sexes share parental duties.

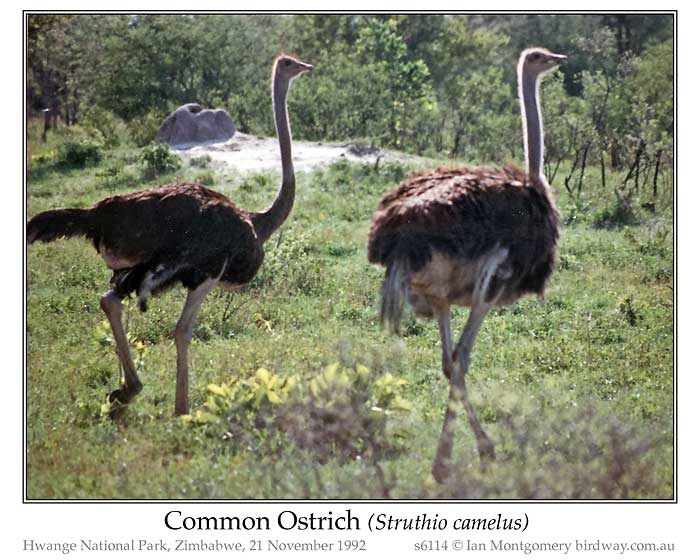

The largest surviving Ratites are the Ostriches, Common and Somali, widespread throughout Africa and formerly also in Arabia, Syria and Iraq. The larger males can reach 2.75m/9ft in length and a hefty 156kg/344lb in weight. Common Ostriches are bred widely for their meat and plumage, and feral populations exist in South Australia and beyond their original range in southern Africa.

Early theories of the evolution of these fairly similar species is that they evolved from a small flying ancestor on Gondwanaland that survived the Cretacious-Paleogene mass extinction about 66 million years ago and took advantage of the space left by the extinction of herbivorous dinosaurs by becoming large and flightless before the evolution of large mammalian predators. Parrots, incidentally, share a similar mainly southern distribution and appear to have originated in Gondwanaland, though their subsequent radiation through continental drift was naturally aided by being able to fly

Needless to say, the story is more complicated than that. Extinct giant members of the group included the Elephant bird of Madagascar and the Moas of New Zealand and there are early ratite-like fossils from the Northern Hemisphere. Existing members include the fowl-like Tinamous of Central and South America which can fly, if reluctantly. The name Ratite comes from the Latin ratis, meaning raft, referring to the flat, keel-less sternum of the flightless species but Tinamous have a keeled sternum. They were formerly excluded from the Ratites but recent genetic studies have confirmed their membership. A better skeletal feature is the unusual, perhaps primitive, palate shared by all of them, which gives the name Palaeognathae, or paleognaths meaning 'old jaw' in Greek to distinguish them from the other clade the Neognathae, 'new jaw', comprising all other extant species of birds.

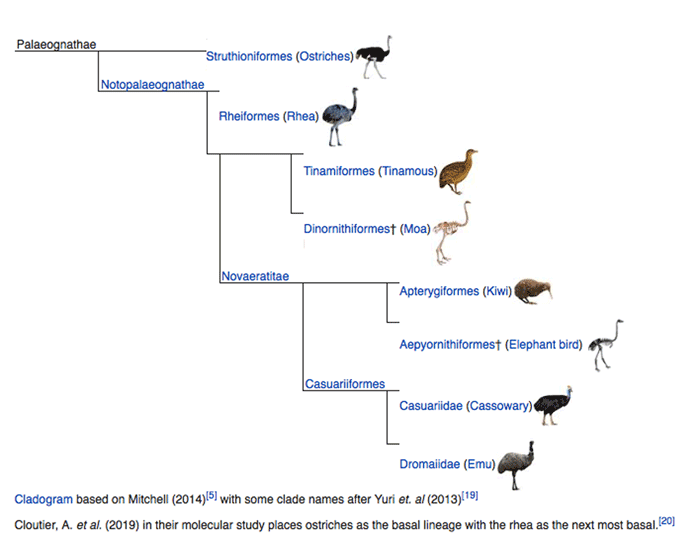

This "cladogram" shows the current understanding of the evolution of the Palaeognathae. The apparent close relationship between the Tinamous of South America and the Moas of New Zealand and the Kiwis of New Zealand and the Elephant birds of Madagascar is truly a biogeographers worst nightmare, worse than the unresolved mystery of the related flightless Kagu of New Caledonia (Birdway: Kagu) and the Sunbittern of South America (Birdway: Sunbittern), which we've considered before (Bird of the Moment #591). Other complications are the two- rather than three-toed feet of Ostriches and the dagger-like inside toe of Cassowaries.

One solution is to propose that flightlessness evolved in parallel perhaps five times in different parts of the world as this is easier to contemplate that the independent re-development of flight in Tinamous from a flightless ancestor. Loss of flight has occurred fairly readily in other groups such as the Dodo and flightless rails, particularly on islands without mammalian predators. Fossils of early flying paleognaths in North America and flightless ratites in Europe and the lack of early fossils in the southern hemisphere support a Laurian rather than Gondwanaland origin of the group. This would be similar to the Marsupials which reached Gondwanaland and thence Australia via South America leaving the American Marsupials such as the Opossums in their wake.

So, I'll leave it with you. If you wish to pursue it, I suggest you study these excellent Wikipedia articles: Palaeognathae and Ratites, from which I got much of information here including the cladogram. I like the idea of unsolved mysteries offered by the natural world to put the all-seeing and all-knowing Homo sapiens in its place, maybe a subtle Gaia's revenge.

Greetings

Ian

Join the The Irregular Bird Club

Birdway has a free Irregular Bird - formerly Bird of the Moment/Week - Club, enjoyed around the world since 2002 by currently 1000 members. An illustrated article is sent to club members at intervals. The photos are significantly better quality images than those on this web page which are compressed more for faster loading.

The club is a Google Group called Birdway to which only Ian can post. To join the group, enter your email address in the Google box below and click the Join button. This will take you to the Google Group joining page for confirmation. Alternatively, email Ian directly using the Contact link below and he'll gladly do it for you and answer any questions.

Ian also uses the Irregular Bird to keep club members up to date with developments, such as improvements to the website and publication of ebooks. He will not reveal your email address to anyone else nor use it for any other purpose.

Page revised on 25 March 2020

Hide

Hide